And so it with a sense of being in total alignment with the zeitgeist that I unveil this list of not-so-secret “secrets”of gardening for wildlife. Drawn from experience in my own garden over the years, I hope that these tips will prove useful to anyone who wants to attract (and support) more bugs, birds, lizards and other wild animals through their gardening practices.

Make it a Habitat The Secrets of Native Gardening for Wildlife

A resident Western Fence Lizard strikes a pose in the LANPS garden

It seems nearly every other documentary these days has the word “Secrets” in its title, as in “Secrets of the Pyramids,” or “Secrets of Hampton Court Palace,” or “Secrets of…” well, you get the idea. Something these documentaries also happen to have in common is a distinct lack of any actual secrets.

San Bernardino Larkspur (Delphinium parryi) intermingling with local stalwart Black Sage (Salvia mellifera)

Secret Number 1: Plant the plants that grow where you live

Planting locally native species is undoubtedly the sine qua non of habitat gardening. Many animals rely upon those plant species with which they have co-evolved over eons. While imported exotic insects like the generalist European Honey Bee may be able to forage on pretty much whatever happens to be available, many local species depend upon specific plants for their sustenance and survival. The uniquely exclusive relationship between Milkweeds and Monarch Butterflies is, perhaps, the most well known, but as a general principle, a successful habitat gardener will provide local wildlife with the plants they instinctively recognize as food.

If you’re not sure what plants are truly native to your particular gardening location, go to calscape.org, and click on “Find Native Plants.” Simply enter your zip code, et voila: you’ll get long, somewhat overwhelming list of plant names ready to choose from as you create or expand your local (or local-ish) plant palette. (And when I say “long,” I mean long: according to Calscape, the LANPS garden’s puny zip code is home to over 700 different plant species!)

Masses of Goldfields and Blue Dicks are easier for this Tiger Swallowtail to spot

Secret Number 2: Plant More Than One

Before you go wild planting as many species from your Calscape list as you can cram into your necessarily limited amount of gardening space, consider that the micro-environments within a given wild landscape typically feature a relatively narrow, repeating subset of plants that are well suited to its particular conditions. In addition, the fact that plants are stationary lifeforms means their proliferation strategies, while clever, are somewhat limited in scope. Whether via dehiscing seed or rhizomatous expansion, plant species tend to spread gradually outward into the immediate area surrounding the mother plant. This dovetails nicely with the fact that masses of the same flower color are easier for pollinators to recognize than isolated specimens. More botanical repetition means more pollinators, which means more birds and so on, right on up the food chain.

In other words, a “one-of-each” native botanical garden, while visually pleasing to your variety-loving human visitors, will likely prove much less appealing to the wildlife in your vicinity. Admittedly, limiting the number of different species in your garden to make room for multiples takes a little self-discipline – especially if you have limited space – but if your objective is to attract and support wildlife, you might consider foregoing novelty in favor of repetition at least some of the time. When it comes to habitat gardening, less is definitely more.

Put that rake away

Secret Number 3: Keep it Messy

Tidiness may be a virtue indoors, but when it comes to habitat gardening, the messier the better. Taking your cue from the natural world, with its thick carpets of dead leaves, tangles of fallen branches, snags and impenetrable thickets, resist the temptation to impose more order on your garden than is absolutely necessary for access and safety. From providing food for bacteria, fungi, earthworms and insect larvae to furnishing the building materials for nests and warrens, garden detritus, when left in situ, will restore the vital cycle of growth and decay to your miniature ecosystem while giving your soil an endless source of nutrients. (See “Snag Party” for more on the virtues of garden decomposition.)

Pro Tip: The appropriately named Western Fence Lizard seems to have an affinity for stacks of wood. If you pile up a few branches you’ve pruned, or even some scrap lumber here and there, you may get a reptilian tenant or two, at least until the whole thing decomposes. Just make sure there are lots of nooks and crannies they can call home. Also on the “Keep it Messy” front: try to refrain from reflexively clearing spiderwebs away. Hummingbirds like to use them when building their nests.

Scads of spherical seeds embedded in the ghostly scaffolding of a spent Caterpillar Phacelia (Phacelia cicutaria)

Secret Number 4: Let your plants go to seed

As a figure of speech, letting something “go to seed” is generally taken to mean that the thing in question is being neglected. When taken literally, however it describes one of the most important of habitat gardening tenets: allow your annuals and grasses the time they need to go through their entire reproductive cycle – from flowering to fruiting to the broadcasting of mature seed – before you prune or trim them back for reasons of fire safety (or, let’s face it, for aesthetic considerations).

Similarly, the flowering stalks of perennials, such as sages and, buckwheats, should be left to completely dry out and dehisce before deadheading whenever possible. This practice is virtually guaranteed to attract mated couples of ground-foraging birds like California Towhees and Mourning Doves. Finches seem to prefer devouring seeds before they drop, so be sure to leave some seed heads to mature on the stalk in Lamiaceae and Asteraceae species like sages and sunflowers. And while the berries produced by species like Golden Currant (Ribes aureum) and Blue Elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea)are extremely attractive to birds as they ripen, leaving whatever fruit they’ve left behind by the end of the season to fall to the ground will further contribute to an “all-you-can-eat” garden floor.

Pro Tip: If and when you do cut your spring ephemerals and grasses to the ground in early summer, be sure to leave some of the trimmings on the ground here and there as a kind of nest-building Home Depot.

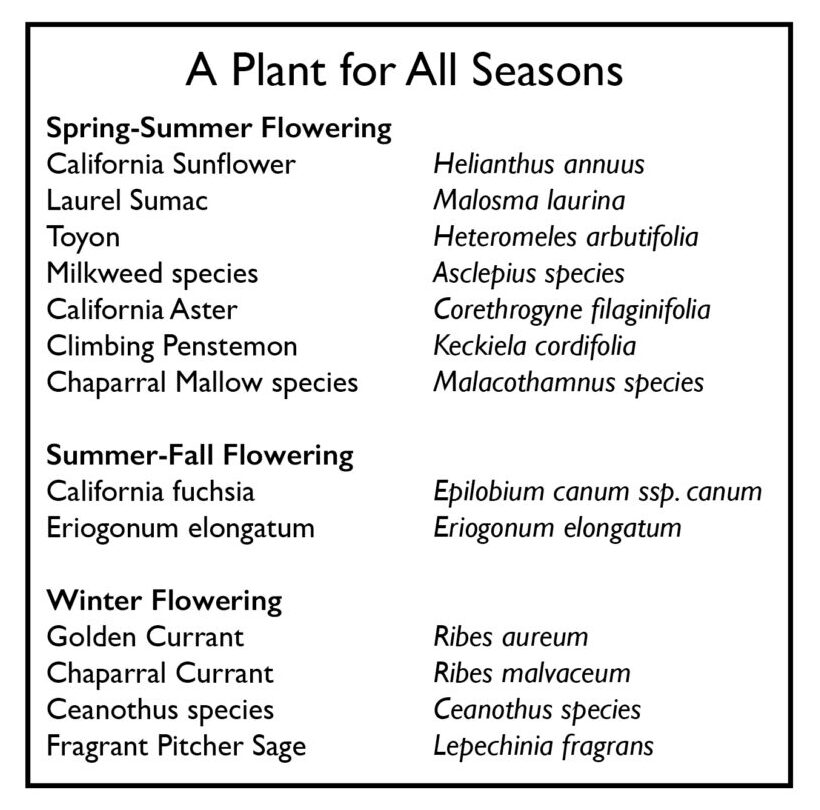

Secret Number 5: Plant so that there is always something flowering in your garden

We all associate flowers with spring, and there are certainly more of them in April and May than at any other time of year. For pollinators in particular, spring is truly a groaning board. But what about the rest of the year? Making sure your habitat garden includes plants that flower in the winter, summer and fall will keep those same pollinators content and less likely to wander off in search of sustenance elsewhere once spring’s extravagant display has wound down.

Pro Tip: By far the best LA-local species for late-summer/fall is Longstem Buckwheat (Eriogonum elongatum), which flowers when there is little to nothing else in bloom.

Secret Number 6: Just Add Water

One of the most harmful consequences of the wholesale development of wild land in the Los Angeles area over the past century has been the destruction of the region’s freely flowing waterways. It follows that offering local wildlife a reliable source of water will draw them to your garden and keep them coming back for more. Birds in particular will literally flock to birdbaths, ponds and fountains, especially in warm weather, and they have the ability to recall the precise location of water sources over time for return visits. Adding movement to the water with a simple, immersible pump or solar fountain gizmo will increase the allure of whatever water feature you have exponentially, as birds find the sound and sparkle of splashing water to be utterly irresistible.

Oh, and unless you want a one-star review from your avian visitors, remember to change out the water in standing basins roughly every other day and scrub them with a gentle disinfectant (such as a 10-1 water/vinegar dilution) from time to time.

By adding water to food and shelter, you’re completing the “habitat triangle,” and basically creating an “Amazon Prime” habitat garden, where everything wildlife could possible want or need can be found all in one place. Anthropomorphizing for a moment, you want the animals visiting your garden to think, “Why on earth would I go anywhere else?”

Pro Tip: Create a watering hole for butterflies and bees by regularly dousing a bare patch of dirt in your garden throughout the summer. If possible, choose a spot with slow drainage so that you end up with a constant patch of wet mud, the lepidopterous equivalent of a dive bar.

The LANPS bird fountain is a popular spot for cooling off on a hot day

Secret Number 7: Be careful what you wish for

The biggest problem with gardens designed to attract wildlife is that…they attract wildlife. You may enjoy the satisfaction of seeing a bunch of Cedar Waxwings frolicking in your bird bath, but be prepared for the possibility that that same water feature may also attract a family of raccoons who will move in, enthusiastically dig up your young plants and generally use your entire garden as their own personal salad bar. In creating an environment that supports the wildlife you do like, you may end up unintentionally putting out the welcome mat for those you don’t like quite so much, such as coyotes, skunks, possums, squirrels, rats and other urban “pests” who, while fun to observe, can be enormously destructive to a garden.

Acknowledging that creating a wildlife habitat in your backyard may result in unintended and less-than-desirable consequences can help prepare you for the inevitable complications that come with the territory. Hopefully, the joy (and importance) of creating a living habitat for our beleaguered animal neighbors will outweigh whatever nuisances you may encounter in the process.

– Eric Ameria

© 2025 by LA Native Plant Source